Underground Earthquake

In the evening of October 23, 1958, a bump wracked No. 2 mine in Springhill. The underground earthquake sent floors, ceilings, and walls to meet each other, opened great chasms, poured coal and debris into open spaces to completely block levels, and cut off all communication below 7800 feet. In the immediate aftermath, 81 men made their way to the surface. Then from the deeps was only silence.

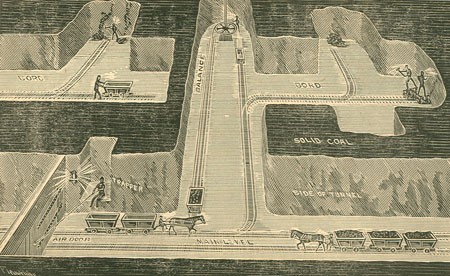

No. 2 was an old mine, and at 14,300 feet, believed to be the deepest in the world. This depth, combined with its average pitch of 25 degrees, made the mine prone to small “bumps”. A coal mine bump is an underground earthquake, causing substantial movement in the earth. The violent upheaval can bring pillars, roofs, and walls of a coal mine crashing down, raise floors into roofs, and toss men and machinery around, causing death and devastation.

Fatal Mistake

Since 1952 ten men had died in bumps in No. 2 Mine. The pattern of mining there had recently changed. Previously the walls were being worked in a step-like way, so that if there was a bump, it would be confined to that one wall. However, the engineering department changed the mining to one long wall, expecting that the roof would fall in behind and ease the pressure that caused small bumps. The roof did not fall in behind; instead, there was one gigantic cataclysm.

Miners Survive Several Days Awaiting Rescue

Rescuers included draegermen to break into sealed spaces, but mostly barefaced workers to excavate every corner over the mine in case men were alive in a sealed pocket, kept alive by compressed air. After six days of arduous digging and finding only bodies, voices heard through a pipe led to the discovery and rescue of twelve men entombed at the 13,000-foot level.

Three days later, seven more living miners were uncovered. Throughout their lengthy ordeal the trapped men had kept their hopes alive singing, praying, and banging on pipes in efforts to be heard. 75 died in this bump. No. 2 mine was not reopened.

Immortalizing the Tragedy

Upon word of the bump, media flocked to Springhill. From the pithead, the CBC television did their first ever international live broadcast, bringing the unfolding drama into people’s living rooms. As hearts far and wide were caught up in the story, and in its two miracle rescues, the working man’s disaster spawned poetry and music.

At least nine songs commemorate the event. Most notable is The Ballad of Springhill, composed by the renowned folk singer and multi-instrumentalist Peggy Seeger and performed by her and her songwriter-husband Ewan MacColl at the 1960 Newport Folk Festival.