First Recorded Mine Disaster

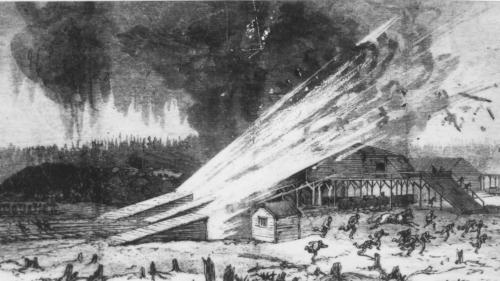

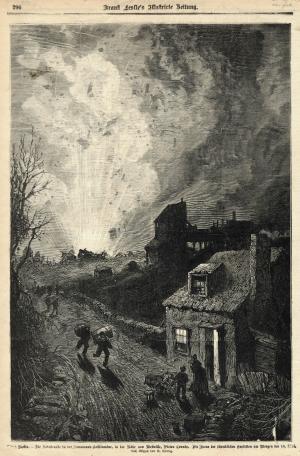

Canada’s first recorded mine disaster happened in Westville, Nova Scotia on May 13, 1873. At 11:45 a.m. that morning, three shots fired into a coal face “did not blow well”. One of them smoldered, setting methane, then coal, on fire. Fed by oozing methane, the coal fire spread quickly. While a group stayed behind to fight the blaze, miners left their smoke-filled workplaces. As they walked up the slope, some men, overpowered by smoke and carbon monoxide, collapsed, dying. Before many could reach the surface, a massive gas explosion fueled by coal dust roared through the mine. Flames and smoke poured straight out the pit mouth, hurling equipment and timbers high in the air. Young miner Peter Barrett recorded in his diary, “Dense volumes of smoke were coming up the slopes ... buildings were shattered ... the high brick air stack was blown down.” A report described “unexampled on this continent for violence ... dealing on all sides death and destruction”. (Peter Barrett, Twelve Years in North America, NS Archives, MG1, vol. 3196A.)

A Second Explosion

After the explosion, only three men got safely out of the mine. As the Drummond officials were below in the wrecked pit, managers from nearby companies organized a rescue effort. Four men volunteered to descend the pump shaft, to explore conditions and for possible survivors. They were hardly gone when a second massive explosion wracked the pit. Smoke and flames rose from every mine opening, and as Barrett described, “blowing up debris ... hundreds of feet high into the air, carrying away in its fury, the gin, and all of the gearing of the shaft head..., and as we ran for our lives, the debris fell all around us.”, including the body of one of the pump-shaft volunteers.

Delayed Recovery Efforts

Buildings and outcrops flamed for 36 hours before the fires could be put out. Water was pumped down until the mine could be sealed. In October one slope was reopened and ventilation resumed, but fire still burned. The mine was cautiously reopened and recovered the next spring. Over the next several months, bodies were located and removed.

60 men and boys, and horses were killed in the explosion. The Coroner’s Inquest found the initial blast was caused by “an explosion of gas ... caused by derangement of ventilation in the mine, arising from the fire” in the bord. The Jury “express(ed) their regret” that powder was permitted in this area. Although it had been tested and considered safe before that day’s mining, the area had been known to be gassy and blasting had indeed been suspended on a previous occasion. Its reinstatement suggests that safety was compromised for production.