Methane a Problem From the Beginning

The General Mining Association (GMA) began sinking its state-of-the-art Foord mine in 1867. Early in its development, on March 27, 1869 a gas explosion and fires forced the pit’s closure for two months. Methane was an ongoing hazard over the next years. This was mitigated somewhat by a new Guibal fan installed in 1873 by new owners, the Halifax Company. This suction fan pulled gas from the mine.

An Ill-Fated Year

1880 proved an ill-fated year for the Foord. On May 21, three men were badly burned when a fired shot ignited methane. On September 15, when mining broke into abandoned workings of the Dalhousie pit, water rushed in, killing nine horses and causing heavy damage. On October 12, a similar flood occurred when a barrier with old Bye Pit workings burst. Six miners perished.

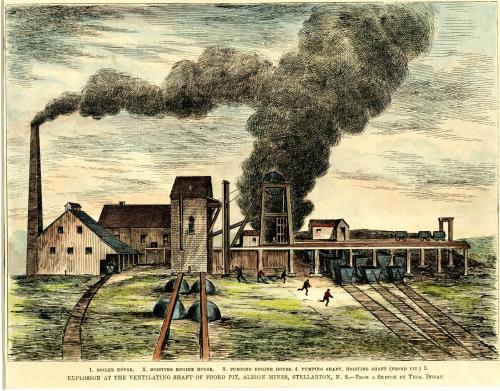

On Friday, November 12, workers on the surface were shocked by a great roar, just as a blast of air gusted from the fan shaft, blowing off the roof and the side of the fan house. The Foord Pit had exploded.

Luckily the fan kept operating, drawing out carbon monoxide and thus protecting men on the north side of the Foord from breathing the deadly gas stealing through the mine from fires on the south side. Because the Foord was connected underground to the Cage Pit, miners on the north side were able to escape via the Cage Pit workings and Cage miners were evacuated.

A small group went tentatively below to search. They found a few men insensible from gas, but alive, near bottom on the south side, then only lifeless bodies. Suddenly, the rescuers felt explosive action deeper in the mine, and had to run for their lives to the lift.

After three hours, seven mine officials ventured down. On the north side they found two living men and several dead horses, but the south side remained inaccessible due to carbon monoxide. Another foray that night also was futile. When on Saturday morning a team descended, they were driven out by black smoke: the mine was on fire. Smoke rising high out of the shaft could be seen as far away as Pictou (approximately 20 kilometres). With the fire anticipated to spread to the Cage Pit, their pit horses were brought out.

Aftermath

All mine entrances were sealed. The plan was to flood the pit from the East River and trench-digging got underway. A violent explosion late Saturday night blew off the seals, hurling timbers, bricks, metal, and canvas into the night and further damaging the fan house.

The mine was re-sealed on Sunday afternoon and local fire departments were on the scene with their steam pumps drawing water through hoses from the East River into the fiery pit. A few hours later yet another explosion blew off the seals and threw up materials, wrecking more surface buildings. Smoke continued to seep from the shaft covers until Tuesday morning when the trenches were finally finished. Water poured from the river into the old Bye Pit, and from there into the Foord, gradually extinguishing the fires.

The number of miners killed varies among reports, but at least 44 perished. Although the inquest jury found the “fire damp” (methane) explosion accidental, it made eleven recommendations. Many related to safety, inspection, examination of officials, and training were later incorporated in the Nova Scotia Coal Mines Regulation Act.

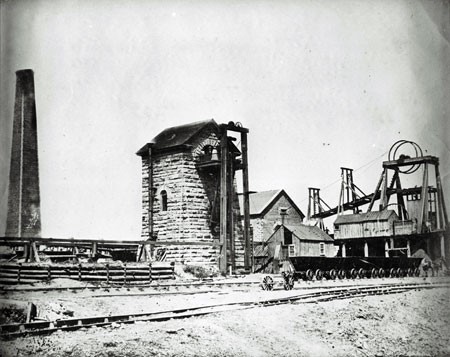

Over the next 16 years several attempts were made to reopen the Foord and Cage, but thwarted by fires and explosion, the mines were sealed for good. The remnants of the Foord Pit’s acclaimed Cornish pumphouse were moved to the grounds of the Museum of Industry when the Trans-Canada Highway was twinned in the area in the late 1980s.